The Extraordinary Shift

It all begins with an idea.

How the Evidence for the Resurrection Made Me a Christian

By Tyler DiPietrantonio

I was not raised a Christian, and in my entire life up until recently I had never confessed Christ. But confess Christ I eventually did, and was officially baptized this past November. How the Holy Spirit changes the heart of the unregenerate is different for each person. For myself, I have always had an analytical disposition. Facts and logic are important, and although I would have scoffed at it for much of my life, Christianity is a religion that is uniquely testable against facts. Being raised non-religious, and becoming an ardent atheist in my teenage years, this was a fact that eluded me for most of my life. But thanks to God’s general revelation in nature, as explicated by the Apostle Paul in the first chapter of his epistle to the Romans, I eventually came to realize the poverty of that worldview. It was then that my mind was opened to the facts of Christianity. Perhaps you are a skeptic like I once was, or perhaps you were raised Christian but do not know of the historical evidence that testifies to the resurrection. This account is written to introduce you to some of the evidence that convinced this former dyed in the wool skeptic of Christianity.

Stephen Hawking

My journey from atheism to Christianity was not a sudden and radical conversion moment. That is, not like the sudden volte face enacted by the Apostle Paul when he encountered the risen Christ on the road to Damascus. I became an atheist as a teenager after having been raised non-religiously, but by my mid-late twenties I was seeing serious deficiencies in the worldview I had long championed. Particularly in cosmology, the increasingly clear evidence that our universe began to exist, and has laws which exhibit an extraordinary degree of fine tuning for life to exist, did not appear intelligible within a materialistic worldview. It was when I read Stephen Hawking’s “The Grand Design,” which purported to show otherwise, that I fully grasped how hopeless the whole endeavor was. There is pulling the wool over your audience’s eyes, and then there is telling them “as long as there exists a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing.” To see such an eminent physicist attempt to sway his readers with such transparent gibberish was more than a little disconcerting, and I found it easier than ever to relinquish the notion that the material world and its regularities are all that there is.

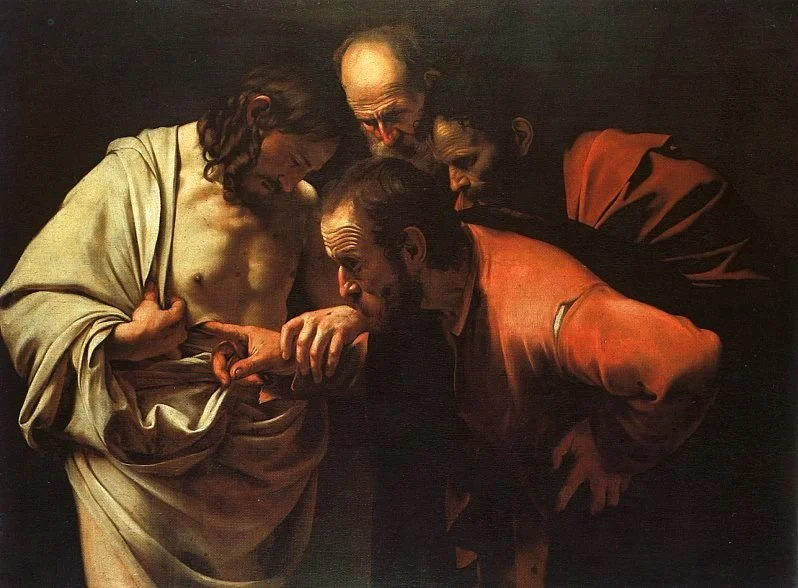

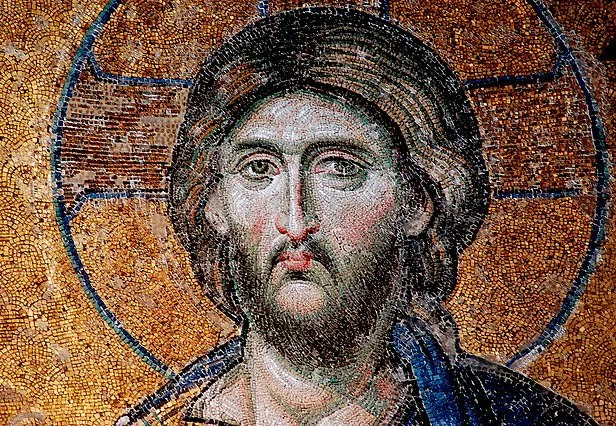

Caravaggio’s “The Incredulity of St. Thomas”

But while that did upset my intellectual apple cart quite a bit, it did not immediately make me a Christian. I would in fact spend years drifting further and further towards what may be called a “philosophical theism.” It was when I was already advanced well into this direction that the COVID-19 pandemic began, and I swiftly found myself, like everyone else, in a world that was completely turned upside down. The combination of the sheer weight of these events, and the unanticipated amount of free time it all afforded me, resulted in my taking the opportunity to address the metaphysical and spiritual questions I had been keeping at arms length. It seemed at the time quite difficult to reach the conclusion that Christianity or any other particular religion was completely true, and I would initially scoff at just that proposal. It wasn’t until I saw a video of William Lane Craig presenting his “four basic facts” argument for the resurrection that I began to take serious notice of the issue. Although I was not initially convinced, it provided an impetus for further investigation that ultimately led me to meet Jesus, and I subsequently became a Christian.

When I would not have called myself a Christian, I took for granted what may be termed the “growing legend” view of the Christian proclamation. That is, the notion that Jesus gradually attained deity as his followers struggled to rationalize the fact that the man they believed was the Messiah had been crucified (I had actually learned much earlier than this that the idea that Jesus did not exist at all, though popular in internet atheist circles, is not taken seriously even by secular scholars). It was a gigantic “game of telephone” where “anonymous” stories circulated until, sometime in the late first century AD, out popped something resembling the Christianity with which we are familiar. It was Brant Pitre’s book, “The Case for Jesus,” that completely disabused me of this view. I highly recommend Pitre’s book to everyone, as it is not only highly accessible, but a scholarly tour de force that dismantles many of the oft-repeated skeptical canards regarding the Gospels. Pitre carefully and clearly dismantles claims that the Gospels were initially anonymous, that they must be dated later (post-70 AD), that Jesus is not divine in the synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke) but is in John, and many other claims. Thus, while William Lane Craig loosened the bolts, Dr. Pitre blew the door off my skeptical presuppositions completely, and more than any other author he can be credited with making me a Christian.

But of course, I did not stop there. Such a radical change in worldview created a hunger for more information. I had also, for instance, read Peter J. Williams’ “Can We Trust the Gospels,” another accessible and also very concise book that shows how the Gospel writers accurately portray so many details about pre-70 AD Jerusalem that we are hard pressed to argue that they shouldn’t be taken as reliable historical sources. The Gospels show an intimate familiarity with Palestinian topography, accurately date events, intuitively navigate the chaotic political situation of Roman occupied Judea, and much more. Together these two books were crucial in convincing me that the New Testament documents, particularly the Gospels, should be taken as reliable eyewitness accounts of Jesus’ ministry and what his followers experienced. There are other, longer, and more technical books that I also think Christians should read, such as Richard Bauckham’s “Jesus and the Eyewitnesses” and N.T. Wright’s “The Resurrection of the Son of God,” but as these books are shorter and more accessible, they pack more of a punch for a beginner, and I recommend that seekers begin their inquiry with them if they are interested in history.

But once we accept that the Gospels and other New Testament documents provide us with a robustly reliable account of Jesus’ life and deeds, and don’t represent some telephone-game-like growing legend among anonymous storytellers, we have to seriously reckon with several facts. The first, and surprisingly one of the more widely accepted, is that the tomb was found empty on the Sunday following Jesus’ crucifixion. This turns out to be the case because there are so many independent lines of collateral evidence that support it in addition to the New Testament witness. For instance, it is difficult to see how the Christian message could be preached from Jerusalem (as confirmed by the Roman historian Tacitus and the Jewish historian Josephus) if Jesus’ body was actually still present in the tomb. There is also the fact that early Christians, as seen in the Gospel of Matthew as well as Justin Martyr and Tertullian later in the second century, find themselves having to fight off an accusation by Jewish critics that the disciples stole the body, an accusation which presumes and thus tacitly admits to the tomb’s emptiness. Celsus, a major second century critic of Christianity, also attempts to explain away rather than deny the empty tomb, which is crucial because Celsus drew upon Jewish sources (according to the great church father Origen, who preserved Celsus’ words at length in his rebuttal “Contra Celsum”). But among the most compelling evidences for the empty tomb is as subtle as it is surprising: its discovery by women in all four Gospel accounts. In the ancient world, Jewish and Pagan alike, women’s testimony was considered practically worthless, making it wholly unlikely that the story was simply made up to win converts. These and other lines of evidence are why William Lane Craig can confidently claim that a broad spectrum of scholarly opinion now grants the historicity of the empty tomb.

But by itself, this would not be entirely sufficient to establish the truth of the Christian faith. A mysterious and inexplicable disappearance of a body may be highly disconcerting, but it is in the end just that (indeed, with the exception of John’s apparently personal account of his own reaction in his Gospel at verse 20:8, the empty tomb does not appear to convince any of the disciples). It is the behavior of the disciples after this and the claims about what they experienced that push us to take them wholly seriously. After their leader had died the ignominious death of a common criminal, in a manner that the Mosaic law explicitly states accounts someone as cursed by God (Deuteronomy 21:22-23), they were preaching a new message in face of hostile audiences: the man the Jewish authorities had demanded be crucified had risen from the dead, and they had seen him. These appearances are recalled in no less than six independent accounts: the four Gospels themselves, the sermon summaries found in the book of Acts, and a creed quoted by the Apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 15, which many scholars date to as early a few months after the cross (see, for instance, Mike Licona’s “The Resurrection of Jesus”). These appearances, where described in detail, are absolutely striking in their vividness, involving eating and drinking, physical contact, lengthy conversations, and sustained, up close interactions in group settings, sometimes with witnesses numbering into the hundreds! Given that the early disciples faced the prospect of persecution from both Jewish and Roman authorities for the message they were preaching (as confirmed even by Roman historians like Tacitus and Pliny the Younger), one must take them as entirely sincere in their claim to have seen these things. One is highly unlikely to voluntarily suffer and die for something they know to be false.

Many attempts have been made to account for these facts without granting the resurrection, but they are all found wanting. It could be postulated, and often has, that the disciples simply hallucinated these appearances. But the hallucinations documented in the medical literature do not easily fit for several reasons. First, what are called multimodal hallucinations (that involve two or more senses, like sight and touch) are extremely rare, and group hallucinations have apparently never been documented (see again, Mike Licona, pp 484-486). These would also not be sufficient to explain the empty tomb. One could posit that a conspiracy by the disciples removed the body, as the early Jewish polemic asserted, but what would be their motive to do such a thing, when it would place them in imminent danger for no apparent benefit? The authorities themselves could have removed the body, perturbed perhaps by the fact that a convicted blasphemer had been given an honorable burial, but why wouldn’t they simply have produced the body after the disciples had started making a fuss? And then what of the experiences? All of these facts, the disappearance of Jesus’ body, the postmortem experiences of Jesus’ followers, and the voluntary suffering and even death of the original eyewitnesses, are mysterious on their own. That they coincide in the same event must be considered utterly baffling. When one examines the alternatives in detail, one becomes increasingly convinced that the best explanation for the historical data at hand is that Jesus is, indeed, the risen Lord.

Caravaggio, Paul’s Conversion

In the end, we come back to the Apostle Paul himself. Once a persecutor of the new Christian religion, he not only suddenly turned around and embraced the new faith but played a crucial role in spreading it throughout the Roman Empire. In his letter to the Galatians, he states both of these things first hand, and the authenticity of Galatians (along with seven other letters that bear his name) is nearly unquestioned across modern New Testament scholarship. The fact that such a hostile party had embraced such a change in his life, and indeed voluntarily invited suffering and eventual martyrdom to his person for it, is extraordinary and without any clear precedent in the history of world religions. Indeed, although it may be a bold claim, my investigation has increasingly solidified me in this conviction: the sociological and historical facts surrounding Christianity’s emergence and spread in the first century are completely unintelligible if Jesus did not truly rise from the dead. So powerful is this evidence that I myself became a Christian, and I thank God every day for sending me his Holy Spirit and guiding me to it.

If you are like me and you have questions, what are some next steps and resources you could check out?

Check Out Alpha. If you would like to discuss these and other points further, Rise Church will be hosting Alpha at the Rwanda Bean at Thompson’s Point starting Tuesday, Sept 13 at 6p. This is intended to be an environment where Christians and non-Christians alike can discuss spiritual questions in an open environment. I will be there most nights.

Conversation over Coffee. If you would like to meet with me one on one, you can email me at tylerofmanyminds@gmail.com and we can attempt to arrange something.

Reading. Would you like to read and research for yourself? The following is an index of books for further reading, some of them referenced in this article, separated into two groups: those generally shorter and more aimed at general audiences, and those that are longer, more technical, and aimed at scholarly audiences. The latter employ more jargon but are also very information rich, and attentive readers will benefit from their more thorough treatments.

Books suitable for beginners:

The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ, Brant Pitre

Can We Trust the Gospels?, Peter J Williams

Books suitable for more advanced study:

The Resurrection of the Son of God, N.T. Wright

Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony, Richard Bauckham

The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, Mike Licona

Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels, Craig S. Keener